Author: Kate Davis – Casey Cardinia Libraries

The

Vietnam War – one of the most contentious military actions in Australian (and

world) history. From 1962 to 1973, 60,000 Australian soldiers served in this

war. 521 died, and over 3,000 were wounded (1). Hidden among the newly

digitised local history resources – available here in our catalogue - there are a range of interviews

which were conducted by Berwick Secondary School students (names unknown) in

the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. Two of these interviews, perspectives from a

Mr. Denis Lansbury and a Mr. P. Finn, tell a story of the local experiences of

the Vietnam war. Both were asked about their views of Australia’s involvement –

the only difference being that one served, while the other didn’t.

Mr.

Lansbury was conscripted as a National Serviceman and sent to Vietnam at 22

years old. His service record reveals that he served as a Private in the Royal

Australian Army Corps, fighting in Vietnam from February 1968 to February 1969

(2). Mr. Lansbury served a total of 2 years - we can assume he undertook a year

of training in Australia before being deployed.

|

| Ballot balls (marbles) that were used as part of the National Service Scheme. |

The National Service, under which Mr. Lansbury was drafted, was a selective conscription scheme introduced by the Menzies government in 1964. The process was similar to a lottery. Marbles numbered 1-31, each representing a day of a month, were randomly drawn from a barrel. All 20-year-old males whose birthday landed on the number drawn were required to present for service (3). Once 2 years of active service was completed, National Servicemen remained in the Reserves for 3 years (4). Mr. Finn’s experience was different; he was not the right age for conscription and did not want to volunteer. If he had been conscripted, Mr. Finn would have conscientiously objected. Conscientiously objecting, for most of Australia’s involvement in the war, meant jail.

Mr.

Lansbury was posted at Nui Dat, in the Phuoc Tuy province – Australia’s

northernmost base, allocated by the United States. Nui Dat, Vietnamese for

‘small hill’, was the ideal spot for a base designed to break the North

Vietnamese’s stronghold on the surrounding villages (5). Nui Dat was, as Mr.

Lansbury described, relatively close to the border and maintained through

continual patrolling. This severely strained the bases resources (6). At its

peak, Nui Dat was home to 5,000 Australian personnel (7). Mr. Lansbury was part

of a reinforcement unit which undertook ad hoc tasks. He was involved in

protecting civil affairs units, supporting fire support bases, patrolling the

surrounding jungle and searching nearby villages.

|

| Map of Phuoc Tuy province - Nui Dat is in the very centre of the image. |

During

his time overseas, Mr. Lansbury had considerable contact with the Vietnamese

people. Particularly, he said, with the Vietnamese living in the Long Hai

mountains. Mr. Lansbury was not

forthcoming when asked if he was involved in battles during his time in

Vietnam, and understandably so. It can, however, be expected that he was indeed

involved in battles while serving.

|

| Aerial photograph of the Long Hai Mountains, which were a stronghold for the North Vietnamese. |

The

experience of the war on the home front was drastically different than it had

been during previous wars. As Mr. Finn recalled, the media reporting made it

difficult to understand what Australians were experiencing overseas. As the war

progressed, media coverage was enormous - and much of it was distorted. Most of

the coverage in Australia utilised footage of American operations. The

Department of Defence and Army strictly controlled footage of Australian troops

and several media outlets had refused to post journalists in Vietnam long-term

(8), resulting in American footage being aired during Australian news coverage.

Mr.

Finn was able to see that the footage being presented was distorted – for many

others the distinction was much harder. This undoubtedly contributed to the

anti-war movement which was gaining momentum at home. Graphic media coverage

brought the realities of war home like never before (9), forcing more

Australians to believe that the war could not be won. Protests were held as

part of the Vietnam Moratorium Campaign against the war right across Australia.

|

| Vietnam Moratorium Campaign march in Melbourne. |

The

largest took place on May 8, 1970 in major cities Australia-wide and became the

largest public demonstration in Australian history at the time (10). 200,000

people took part. In Melbourne alone, the crowd was 70,000 strong (11). Mr.

Finn reported that he had not attended the protests, but supported the movement

and knew quite a few people who were part of the May 8 protest. Mr. Finn

believed that this campaign proved that a large percentage of the population

disapproved of Australian military involvement in the war. As one might expect,

Mr. Lansbury viewed these protests a little differently. He believed that the

war was lost because it had become so political, noting that ‘socialists’ like

MP Dr. Cairns had severely damaged the cause. Dr. Jim Cairns was the chairman

of the Victorian Vietnam Moratorium Campaign and spoke vehemently against the

war in parliament and at protests (12). Mr. Lansbury did recall that the

Australians fighting in Vietnam were aware of the anti-war campaigns, and were

hopeful it might bring them home.

|

| Dr.

Jim Cairns speaking to attendees at the Vietnam Moratorium Campaign march in

Melbourne. |

Perhaps

the most valuable perspective offered by Mr. Lansbury is related to the

experiences of Vietnam veterans post-war. As many would recall, Vietnam

veterans suffered from psychological and physiological issues long after they

had returned home. A lot of the men Mr. Lansbury fought with had been diagnosed

with cancer and psychological illnesses in the years since. This was not at all

uncommon. Research now suggests that 20 to 30 percent of Vietnam veterans

suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (13). When asked whether his own

health was impacted by his service, Mr. Lansbury’s answer is sobering; he will

never know. He believed he was affected by Agent Orange – a mix of herbicides

and fuel, used as a defoliant to deteriorate the jungle along North Vietnamese

supply lines, so that aerial attacks were precise (14). Mr. Lansbury recalls

that he, and others, would drink and shower from large water tanks at the base,

in an area that defoliant spraying planes frequented. None of these water tanks

had covers.

|

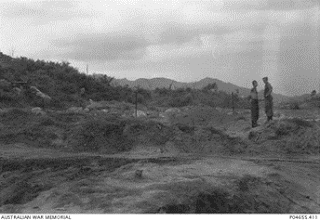

| Photograph of Nui Dat. This looks to be an aerial photograph taken from some distance. The base appears to be in the clearing at the centre of the photograph. |

One

of Mr. Lansbury’s children was born with spina bifida - one of the most common

health impacts in children of Vietnam veterans affected by Agent Orange. Mr.

Lansbury expressed concern for his child; for their health and financial

welfare in the future. He spoke about a recent judgement that had been made

prior to the interview, which sided with the manufacturer of the defoliant. It

is likely Mr. Lansbury was referring to the 1983 Agent Orange Royal Commission.

The Commission had found that the veterans who were exposed did not have worse

health outcomes than the rest of the community. In doing so, in the eyes of

many Vietnam veterans, the government had sided against them. The error in this

ruling would not be acknowledged until 1994 when new medical research found

that the defoliants did, in fact, decrease the health of Vietnam veterans and

their families (15).

|

| Photograph

of defoliated jungle in Vietnam. This shows the devastation the defoliants had

on the land. |

The

outcome of that Royal Commission is incredibly reminiscent of the overall

treatment experienced by Vietnam veterans. Mr. Finn explained that up until the

Vietnam war, soldiers returning home were hailed as heroes; they were met with

jubilation. However, Vietnam veterans were reviled, abused and treated as if

they had created great difficulty in other countries of their own accord. Mr.

Finn’s perspective, unfortunately, rings true. Veterans returned home to a

political environment where the war they had fought was publicly opposed and as

a result, they were shunned. Some branches of the Returned and Services League

of Australia even refused their membership (16). For Mr. Lansbury though,

fighting the war and fighting communism was necessary, even if the Australian

approach was not quite right in hindsight.

When

these interviews were recorded, some recognition of these issues was being

acknowledged. The public had slowly begun to realise the extent of the awful

treatment that was afforded to Vietnam veterans. In 1987, a belated Welcome

Home march was held – sadly too late for many. The Vietnam Forces National

Memorial in Canberra was then built in 1992, dedicated to all who served in

Vietnam (17). In the years since, research has revealed how these returning

home experiences had exacerbated the psychological effects of the war, and led

Vietnam veterans to have much higher levels of psychological illness than

veterans of other wars. These interviews give insight into the experience of a

local Vietnam veteran and of an individual who experienced the war on the home

front. Within the broader context of the Australian experience, these

perspectives give an idea as to how the anti-war movement was viewed, and how

servicemen viewed their own involvement in the Vietnam war.

References

1 - Australian

War Memorial [AWM], ‘Vietnam War 1962-75', AWM [website], 2021, para.

3, https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/event/vietnam

2

- Department of Veteran’s Affairs [DVA], ‘Nominal Roll of Vietnam Veterans’, DVA

[database], 2022, https://nominal-rolls.dva.gov.au/vietnamWar

3 - Education Services Australia

Limited & National Archives of Australia [NAA], ‘National service ballot

balls – the conscription lottery’, NAA [website], 2010, para. 2; para.

3, https://www.naa.gov.au/learn/learning-resources/learning-resource-themes/war/vietnam-war/national-service-ballot-balls-conscription-lottery

4

- National Museum Australia [NMA],

‘Vietnam moratoriums’, NMA [website], 2021, para. 12, https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/vietnam-moratoriums

5 - Department of

Veteran’s Affairs (DVA), ‘Nui Dat’, DVA Anzac Portal [website], 2020,

para. 1; para. 2, https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/vietnam-war-1962-1975/events/phuoc-tuy-province/nui-dat

6

- R. Pelvin, Vietnam:

Australia’s Ten-Year War, 1962-1972, Hardie Grant Books, Richmond, Victoria,

2013, p. 59.

7

- DVA, op. cit., para. 4.

8

– R. Pelvin, op. cit., p. 212.

9

- Ibid, p. 207

10

- NMA, op. cit., para. 1.

11

- Ibid, para. 34.

12 - Australian

Living Peace Museum [ALPM], ‘Voice of opposition to the Vietnam War’, ALPM

[website], n.d., para. 1; para. 2, http://www.livingpeacemuseum.org.au/omeka/exhibits/show/jim-cairns/jim-cairns-voice-opposition

13- D. Dempsey,

When he came home: the impact of war on partners and children of veterans,

Arcadia, North Melbourne, Victoria, 2021, p. 15.

14 – Department of

Veteran’s Affairs (DVA), ‘Agent Orange’, DVA Anzac Portal [website],

2020, para. 2; para. 3, https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/vietnam-war-1962-1975/events/aftermath/agent-orange

15-

R. Pelvin, op. cit., p. 215.

16-

D. Dempsey, op. cit., p. 16.

17-

R. Pelvin, loc. cit.

Photographs

– in order of appearance.

Department

of Labour Central Office, National service ballot marbles [photograph],

October 15, 1994, National Archives of Australia MP1357/63, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=10429230&isAv=N

Edwards, P., Australia

and the Vietnam War, p. 145, New South Publishing, Coogee, New South Wales,

2014.

Gazzard, D.

E., The Long Hai

mountains in Phuoc Tuy province, a Viet Cong stronghold, seen from an RAAF

helicopter gunship [photograph], 1969, Australian War Memorial P01980.012, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C284467

Gilchrist, R., Melbourne, Victoria 1970. Leading

marches at a Vietnam moratorium demonstration in Collins Street [

photograph], 1970, Australian War Memorial P00671.007, https://ww.awm.gov.au/collection/C40178

Gilchrist, R., Melbourne, Victoria 1970. Dr Jim

Cairns MP urges demonstrators at the Vietnam Moratorium march to not clash with

police following attempts by militants among them to break up the peaceful

assembly [photograph], 1970, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C40185

Sedunary, R. L., Nui Dat, Vietnam War, 1970. The American

and Australian Bases at Nui Dat (Small Hill) [photograph], 1970, Australian

War Memorial P00324.006, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C50431

Gibbons, D. S., Operation Finschhafen, 7th

Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (7RAR), first Operation, [photograph],

15 March 1970, Australian War Memorial P04655.411, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1179077

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.